This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on Uruguay

As China’s growth slows and its investments in Europe and North America decline, a debate has emerged over whether Chinese investment and overall economic influence in Latin America and the Caribbean has receded in recent years.

While there has indeed been some decline, it is important to consider the full picture, which is a nuanced one, and in several regards positive. Doing so requires looking closely at recent trends and future trajectories for the four chief pillars of Chinese economic engagement in Latin America: foreign direct investment (FDI), official lending, trade and infrastructure.

Investment holding steady

FDI flows from China to Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) have held steady at levels above $4.5 billion annually on average since 2016, based on our conservative estimates. This is remarkable, considering Chinese investment contracted globally during the same period, particularly in the U.S. and the EU, where it plummeted from over $50 billion per year, combined, to under $15 billion. The relative resilience of LAC enabled the region to gain importance as a destination for Chinese investment. Prior to 2016, LAC represented less than 3% of China’s annual FDI outflows. Now, its share has likely grown to between 5% and 10%.

To put things in perspective, last year China invested $8.4 billion in the EU, $4.7 billion in the U.S. and $7-10 billion in LAC. The fact that LAC would attract a comparable amount of Chinese investment as did the EU and the U.S.—much larger economies—was unimaginable a decade ago. By one estimate, Brazil alone absorbed $5.9 billion of FDI from China in 2021, making it the top recipient country of Chinese investment in the world. After Brazil, other LAC nations, such as Chile, Peru and Argentina, have also received sizable Chinese investments on a regular basis in recent years, with individual mergers and acquisitions transactions representing upwards of $3 billion—such as the Luz del Sur acquisition in Peru and the CGE purchase in Chile.

Several key factors will determine the pace of Chinese dealmaking going forward. On the one hand, our diverse region continues to boast a variety of attractive assets in energy, from conventional to renewables, generation to distribution. Minerals are another promising area, including lithium resources critical to the world’s energy transition, and so is technology (an area of growing interest for Chinese and global investors), among other sectors.

From a geopolitical-regulatory perspective, Chinese investors see LAC as a friendly market, at a time when investment screening has significantly tightened—on grounds of national security concerns—against Chinese investment in the U.S. and the EU. This tightening has contributed to the collapse of Chinese FDI in these regions. In the U.S., for example, China has been subject to major scrutiny by the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States, an inter-agency investment screening committee whose mandate has broadened across different administrations in recent years. As we argued in 2021 in these pages, bilateral tensions between the U.S. and China will likely persist in the foreseeable future.

On the other hand, the region’s governments and businesses should be vigilant about the weakening of the Chinese economy—notably its overall output and credit growth rates, its property sector and its structural rebalancing from an investment and export-led growth model towards a more consumption-based one. Any material deterioration along these lines may subdue Chinese economic activities in LAC, including the volume and size of investment deals (and the channels described below: lending, trade and infrastructure). More broadly, a sharper-than-expected slowdown in China would further complicate an already fragile and uncertain global economic outlook, indirectly impacting risk appetite and access to liquidity for the region.

A dramatic dropoff in loans

A second pillar of China’s economic engagement with LAC is official lending: loans provided by Chinese policy banks to LAC governments. In its heyday, lasting approximately from 2007 to 2016, official lending accounted for the lion’s share of China-LAC financial relations and cooperation, averaging over $10 billion annually. But since then, official credit flows from China to LAC have diminished sharply, dried up completely by 2020 and remained at zero in 2021.

There is an important distinction between official Chinese lending and FDI in the region, despite the fact they’re often used interchangeably: while lending has been trending downwards, FDI has been stable or even increasing. There are also differences in the purposes and beneficiaries of the two. Lending was provided by Chinese public-sector creditors to support LAC public sector projects, and primarily and disproportionately appealed to sovereign borrowers that had trouble enticing international financial markets—such as Venezuela. The country represents less than 10% of regional GDP, yet received over 40% of total Chinese lending to the region.

FDI is more likely to involve the direct participation of companies, whether as investor or investee. While not mutually exclusive, the fact that FDI has overtaken government-to-government lending as the main avenue of China-LAC financial flows is a sign of growing sophistication and private-sector participation in the bilateral economic relationship. It also signals an appetite for the control of foreign real assets that FDI allows for.

Looking ahead, high global costs of capital—both from market and from concessionary sources—could theoretically prompt certain LAC countries to borrow more from China at competitive rates. But Beijing would need a convincing economic argument to reverse the structural scaling-back of official lending to LAC seen over the past years.

One possible explanation of the growing cautiousness of Chinese policy banks in the region is buyer’s remorse. A handful of these early loans, driven arguably more by political than economic fundamentals, had become non-performing. Venezuela is an obvious example. If such cautiousness continues, more official lending activities would take place in the form of renegotiations of existing Chinese lending, rather than the disbursement of fresh loans. For example, in September 2022, Ecuador successfully concluded the restructuring of $4.4 billion in Chinese debt obligations.

Political and other incentives also appear to be lacking to motivate more loans. While loans used to be a thoughtful gesture complementing the visits of senior Chinese officials to LAC, such visits have not occurred since 2020 due to pandemic and zero-COVID travel restrictions. And as the region faces recessionary pressures at the time of this writing, it is unclear at best—based on experiences from the pandemic—whether Beijing really desires to become a global, counter-cyclical lender during economic downturns, a role traditionally played by institutions like the IMF, the World Bank, the IDB and the CAF.

Trade remains robust

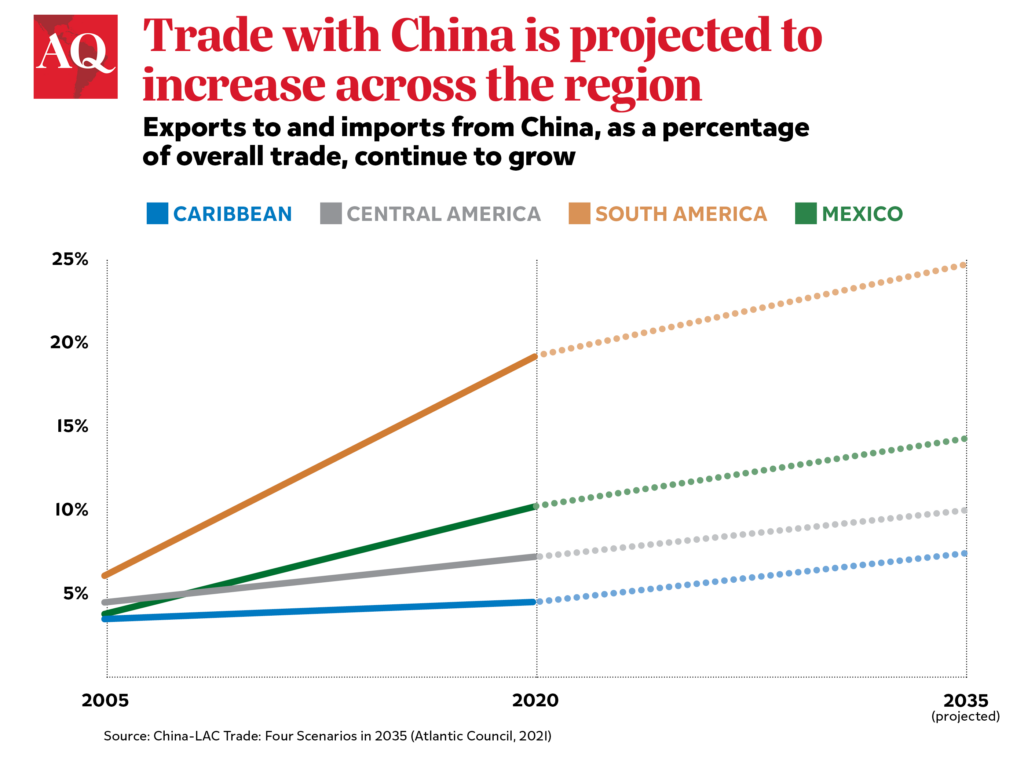

The third and best-established pillar of China’s economic engagement with the region is trade. The exponential growth of the commercial relationship between China and LAC in the past twenty years has underpinned broader bilateral ties and provided a point of entry for Chinese investment and other engagements. Over the years, China has consolidated its position as the dominant trading partner for nations like Chile, Peru, and Brazil, on the back of strong economic complementarity, and is currently negotiating free trade agreements with Uruguay and others while finalizing one with Ecuador. China-LAC trade has been robust and consistently growing, hitting a record high of $450 billion in 2021.

In the short and medium term, trade flows could fluctuate in value as high commodity prices stabilize after the current boom cycle. But long-term prospects for bilateral trade seem very positive, given sustained Chinese demand for LAC products, even despite possible economic deceleration in China. Likewise, from the perspective of LAC consumers and importers, Chinese goods and services exports including technology—from Xiaomi smartphones to apps like TikTok—will likely remain competitive and popular in LAC.

One key consideration for LAC trade officials and private entrepreneurs moving forward is diversification. China’s ability to reliably absorb a great share of South America’s exports (over 30% in Brazil and nearly 40% in Chile) is a testament to the successful trade promotion and facilitation efforts by LAC governments and companies—but it should not become a reason for future complacency.

While recognizing the unique importance of the Chinese market, countries in the region must continuously commit to opening new markets beyond China. In a world increasingly prone to supply chain and geopolitical shocks, overexposure to any single export destination or trade partner is not ideal. Unsurprisingly, projections show that this is a more probable risk for commodity exporters in South America than for other LAC sub-regions.

China still ahead of competitors on infrastructure

Last but not least, China has been successful in fortifying relations with LAC by actively participating in the region’s infrastructure public tenders. Chinese construction firms have won numerous high-profile bids, including the Bogotá Metro, Colombia’s largest infrastructure project. In Chile, China Railway Construction Corporation (CRCC) alone has recently been awarded concessions such as the renovation of the Ruta 5 Sur toll road between Talca and Chillán in 2020, and the construction of a new hospital in Coquimbo in 2022. Both concessions were accompanied by investments, representing overlap with the financing pillars of Chinese engagement described earlier. In a region with considerable infrastructure needs, the visible and strategic nature of these projects—in which U.S. and European bidders were either outcompeted or did not compete at all—more tangibly underscores China’s economic leadership. And at a more macro level, these projects provide China with an additional benefit: the chance to reduce the country’s excess capacity in domestic industrial and construction sectors.

It is crucial for policymakers in Latin America and the Caribbean to maintain a clear-eyed and up-to-date assessment of current economic relations with China—including these four key pillars—with a view to the possible road ahead. This kind of bilateral assessment, based on the specific and varying conditions and priorities of individual countries, can also help governments enhance their broader international economic strategies as persistent U.S.-China tensions play out globally, including in the region.

Finally, as Latin America pursues integration with willing partners abroad, it should not lose sight of the fact that much of its success in attracting foreign investment and trade will depend not only on international actors, but on its own ability to improve domestic fundamentals. Among other factors, a stable macroeconomic, political and regulatory environment is key to that effort.

—

Larraín B., former minister of finance of Chile (2010-14 and 2018-19), is professor of economics at Universidad Católica de Chile, a member of the United Nations Leadership Council for Sustainable Development and the Atlantic Council Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center’s Advisory Council.

Zhang is senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center.